Salastina in Istanbul

/

Salastina: Muse, Philanthropist, or Ottoman-Turkish Concubine?

By Maia Jasper White

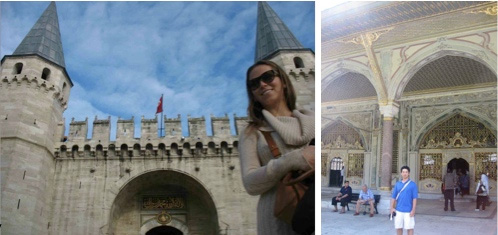

Many of you have asked who (or what) Salastina is. On separate occasions in recent months, Kevin and I traveled to Turkey on what one might call a pilgrimage to our muse and namesake: Istanbul was home to a woman who may have been Salastina. We are delighted to share a bit of the research we unearthed during our Turkish travels with you here.

The history of classical Ottoman palace music, the secular art music that took shape in the courts of the Sultans in the 17th century, has been documented extensively — not only by the Turks themselves, but also by visitors from the West, who could not help but be fascinated by the otherworldly sounds they encountered. As neither Kevin nor I can read Ottoman Turkish, we found French and Italian accounts of Ottoman art music and patronage particularly illuminating.

But first, a bit of background.

Although what is now regarded as classical Ottoman palace music truly took shape in the 17th century, much of the stylistic groundwork was laid in the mid-16th century, during the cultural “Golden Age” of the Ottoman Empire. The conquest of Baghdad in 1530 brought a flood of Persian musicians — and with them, the compositional forms, modes, and instruments of Persia — to the court of Suleiman the Magnificent, then reigning Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. Although it took several more decades for the distinct Ottoman-ness of the music to fully assert itself, it got there with the patronage of Suleiman’s court, and quite possibly with the support of Salastina herself.

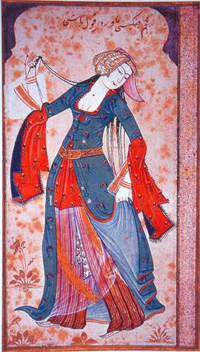

According to documents in the Topkapi Palace archives, the Cemaat-i Mutriban (palace musician’s ensemble) included women playing theçeng – a kind of harp derived from the Persian “chang.” Such çengi were often concubines from the sultan’s harem. Fittingly, the çeng was a common metaphor in Ottoman poetry, representing one doubled over in agony from a lover’s cruelty.

In 1531, a French merchant by the name of Jean du Menton Barbu accompanied the French ambassador on an extended visit to Istanbul. In one particularly poetic diary entry, he describes a woman whom we can not help but assume must be Salastina herself:

Play, Mahidevran, your heavenly harp.

Celestina, pluck your notes from the exquisite canopy of the heavens

with that same divine beauty that draws blood from my heart.

Play me, Rose of Spring, as you play your çeng.

For like it, I am but wood between your knees.

Barbu’s ode tells us that the woman he calls “Celestina” was Mahidevran, also known as Gül-Bahar (“Rose of Spring”). Mahidevran was, for many years, Suleiman the Magnificent’s favorite concubine. She was also the mother of Suleiman’s first-born son, Mustafa. Famously, Suleiman became infatuated with the scheming Roxelana — whose bitter jealousy demanded that the Sultan exile Mahidevran and their son to a remote province. Worse still, Roxelana persuaded Suleiman to have the boy killed, ensuring that one of her own sons would rise to the throne. Distraught over her son’s death, Mahidevran fortunately did not die in poverty. In her later years, Sultan Selim II mercifully put her on a lavish salary.

Little is known of Mahidevran’s early life. She was, most likely, a noblewoman of Adyge/Circassian origin. According to the Human Genome Diversity Panel, Adyges are “not European, Asian, or Russian (Slavic, Cossack) but a different race from the Indo European speaking races altogether.” To this day, one of the most important customs of the Adyge culture is the principle of xabze, which could loosely be interpreted as philanthropy: “the Code requires that all Circassians are taught generosity. Greed, desire for possessions, wealth and ostentation are considered disgraceful by the Xabze code.”

This begs the question: what would a musically-inclined Adyge woman have done with the exorbitant funds bestowed upon her by Sultan Selim II as reparations for his mother Roxelana’s cruelty? This very question adds further credence to our suspicion that Mahidevran may well have been one incarnation of Salastina.

Indeed, Salastina reappears in the Topkapi Palace archives as philanthropist in the following account. In 1573, a Venetian dignitary named Fortunato Baffo-Ossobucco visited the court of Sultan Selim II. (Ossobucco was a distant relative of the Venetian noblewoman Cecilia Venier-Baffo, who was the favored consort of Sultan Selim until his death.) Ossobucco describes a musical scene in the palace:

After dining on a most heavenly stew of beef and marrow bones, we were treated to an exquisite array of aural pleasures. First, the women played on all manner of instruments, plucked, struck, and bowed. Next came the men, just as skilled as their feminine counterparts. As the last note faded into the heavens, a strange Ottoman playing the çeng at my left whispered imperceptibly: “Great is Celestina, for she makes all this possible. Great is the Rose of Spring, whose generosity brings the bud to bloom.”

Does the evidence support that Mahidevran was Salastina? Did Kevin and I stand in the very same room in which our muse enthralled a captive audience, later inspiring and financially supporting generations of musicians to come?